Catalog Information

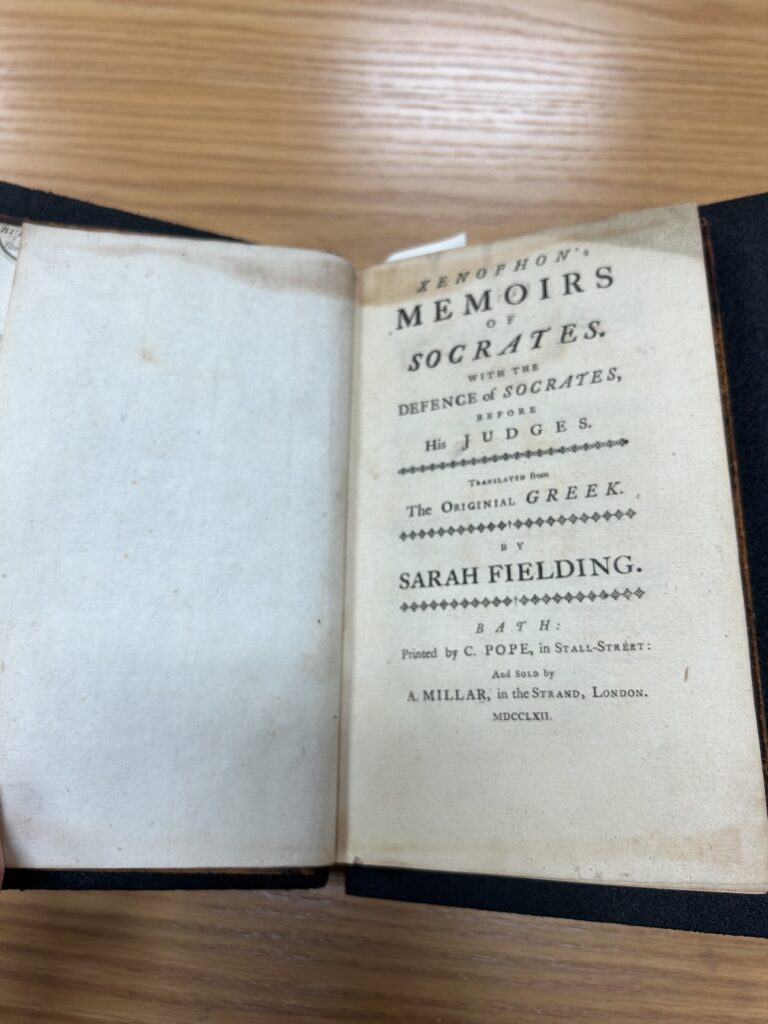

Title: Xenophon’s memoirs of Socrates: with the Defense of Socrates, before his judges. Translated from the original [sic] Greek.

Author: Xenophon; translated by Sarah Fielding

Publisher/Year: Bath: Printed by C. Pope, in Stall-Street. Sold by A. Millar in the Strand, London. 1762.

MSU Holdings: MSU Special Collections; physical copy, microfilm.

ESTC Citation Number: T52845

Library Call Number: B316.X42 1762

Description: 2 unnumbered pages, 8, 2 unnumbered pages, vi, 21, 1 unnumbered page, 339, 1 unnumbered page; 8vo

Notes: First edition. Issued to a list of subscribers. Includes preface by Fielding explaining the choice to translate “Memorabilia” as “Memoirs,” and extolling the classical tradition, among other things. Includes errata list. Includes annotations throughout.

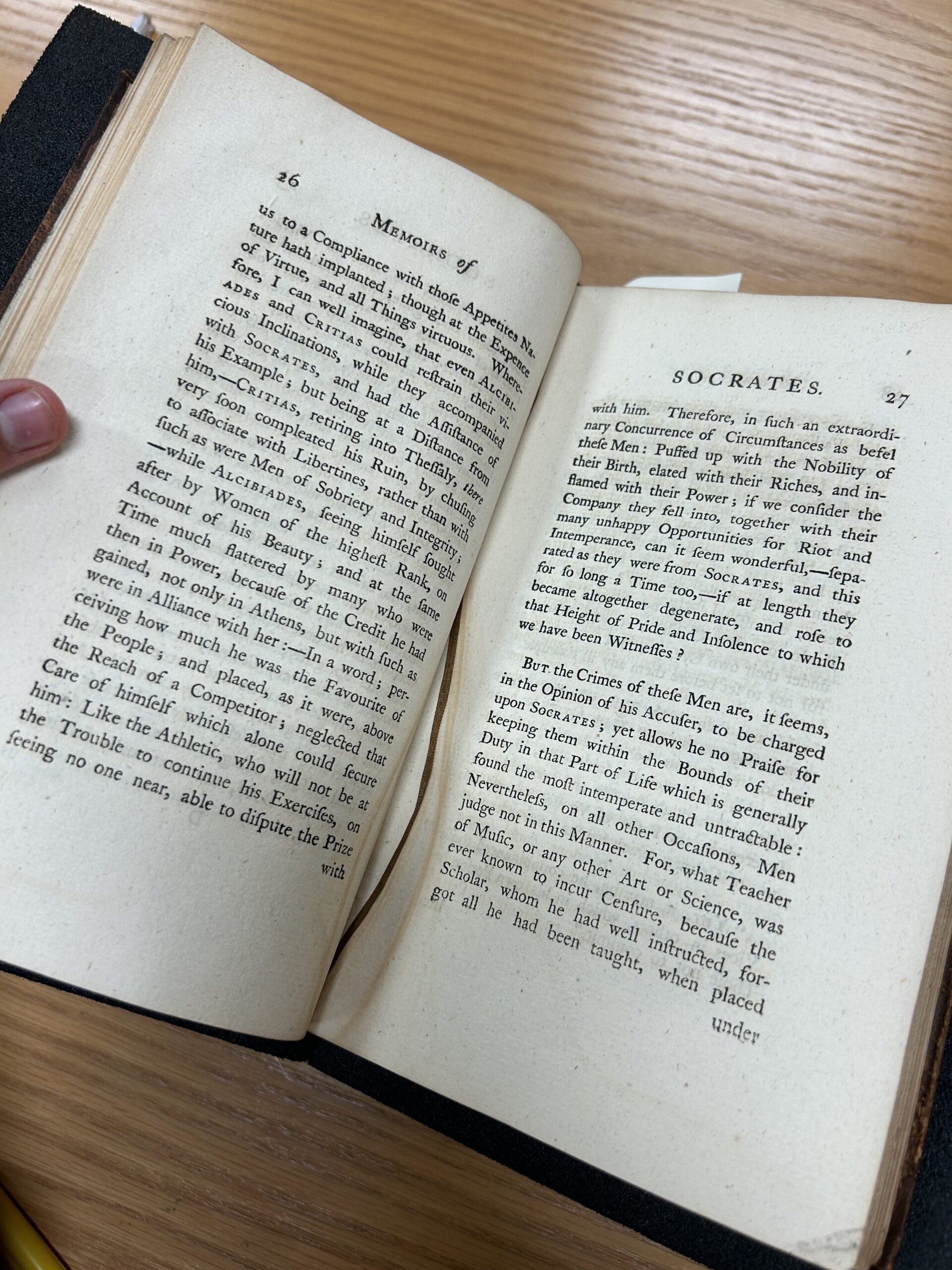

Summary: A preeminent translation of Xenophon’s Memorabilia and Apology of Socrates into English. The only work Fielding published under her own name. The Memorabilia is in 4 books which consist of multiple chapters. The Apology is an addendum at the end. Contains translation notes and references from Fielding.

Subject Headings:

Xenophon. Memorabilia. English (Fielding)

Xenophon. Xenophon’s Apology of Socrates (Fielding)

Xenophon. Memorabilia. Book I. English & Greek

Xenophon–Translations into English.

Bookseller’s Description:

Sarah Fielding’s Translation of Xenophon’s Memoirs of Socrates. Written sometime around 371 BC by Xenophon, a student of Socrates. The memoirs have a dialogical or didactic tone, typical of the Socratic tradition. Xenophon’s anecdotes of his exchanges with Socrates constitute of a philosophizing in their own right. There are four books within the contiguous work, and multiple chapters in each. This edition, translated by Sarah Fielding, has an appended fifth portion at the end. It is the translation of Xenophon’s Apology of Socrates to the Jury, which is a standalone work. It differs from the Memoirs in that the defense is a recollection of the infamous trial of Socrates, after which he was sentenced to death (1). It is much shorter than any of the Memoirs.

Sarah Fielding was a woman of letters and author in Britain in the 18th century. Although she wrote and published her own works, she is perhaps better known as the sister of Henry Fielding, one of the classic English satirists of the Enlightenment (2). She took up the rather industrious task of translating Xenophon’s Memoirs and Defense from Greek, and it was published in 1762 (3). This copy is a first edition from that very year. While the historical record is reticent, we can safely speculate that the works of Xenophon and other mainstays of classical antiquity were sought after during this period. We can say this for a number of reasons: Sarah Fielding’s willingness to translate the work, the printer’s and publisher’s willingness to invest in the undertaking, and the general intellectual and social milieu of the era. To translate Xenophon into English was to legitimize the nation’s claim to the “seat of Enlightenment” and to herald the English as progenitors of the scholastic tradition — something often bestowed on continental philosophy, if we maintain the (admittedly 19th-century) analytic-continental division.

The business of translation brings up a number of issues pertaining to the agency and integrity of the translator. These are especially resonant in the case of Sarah Fielding: she was a woman, she was an author (not solely a translator), and she was translating classical Greek texts, which were often considered the domain of men. It bears pointing out that hers is a translation from the original Greek — not a translation of a translation in a more accessible language, like French. This demonstrates a high level of education and acuity with language, literature, and philosophy. Fielding is certainly “present” within the text. Her voice is most obvious in the preface she wrote, but also comes through in her annotations, which appear regularly throughout the work.

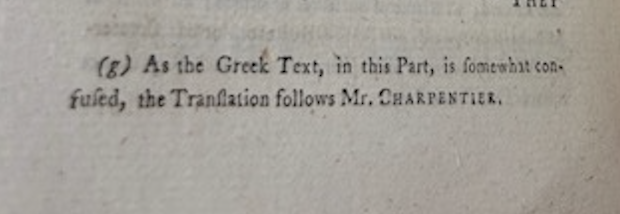

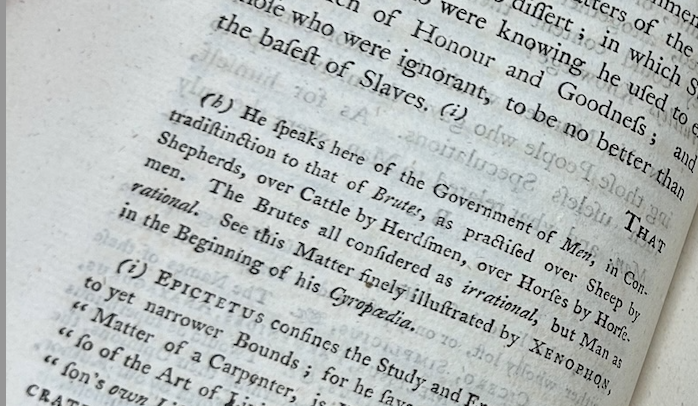

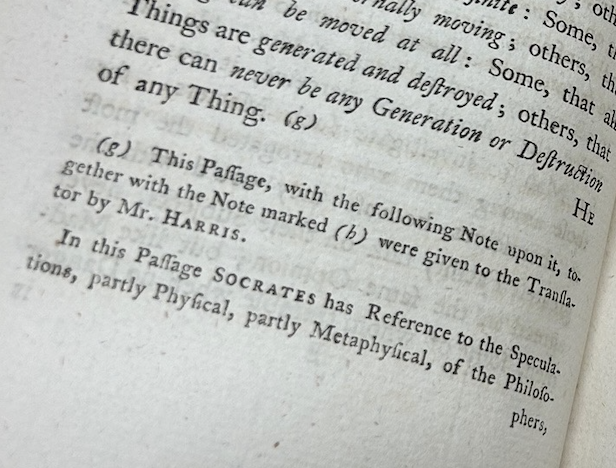

The annotations sometimes reference other classical works or contemporary scholars (Picture 1); she repeatedly cites her mentor, “Mr. Harris” (Picture 2). However, many are her own elaborations on the choices she made in translation, or musings on the text itself. One particularly interesting example is her note on page 12, where she fills in the blanks for Xenophon. Using terms familiar to modern readers, she clarifies what Xenophon supposedly meant by “Government of Men.” (Picture 3) One wonders how much liberty she took with this annotation and to what extent it’s anachronistic. Perhaps in juxtaposing “Government of Men” to “that of Brutes,” Fielding sought to preempt any strictly gendered interpretation of the phrase.

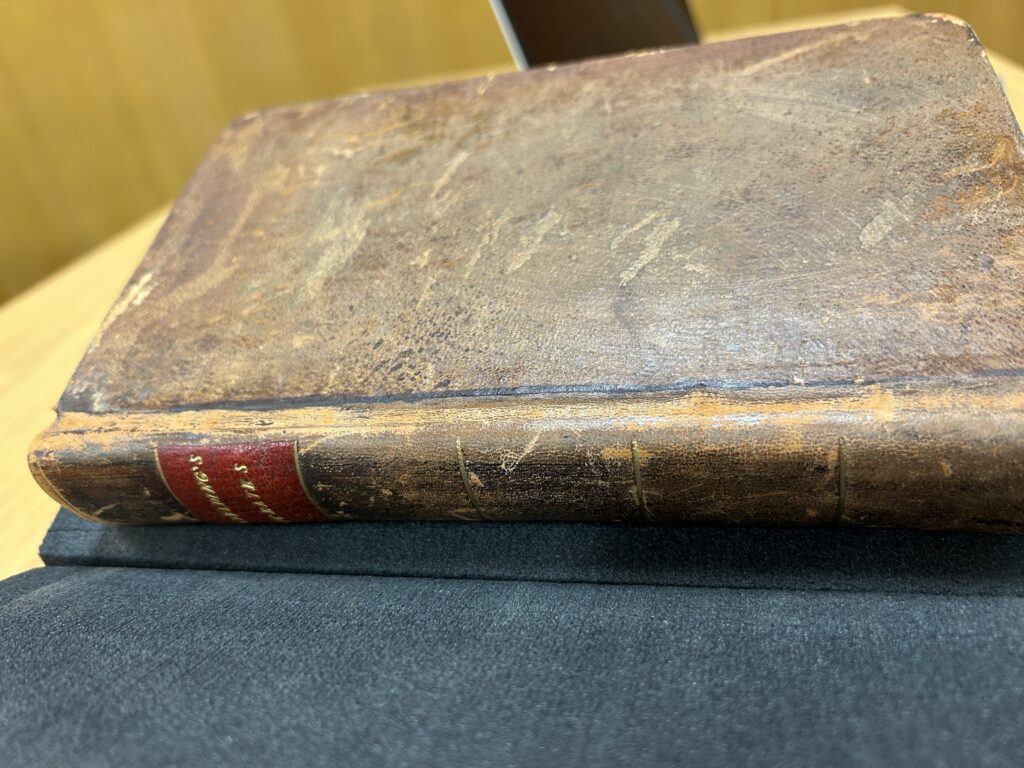

The book itself is in relatively fine condition. While the binding is less than stellar (more on binding later), the quality of the materials used is evident. The paper is quite sturdy, and there are no rips. There is a distinctive odor which evokes vellum, but that seems unlikely given the era of print it comes from. There is moderate spotting on the front pastedown and title page (pictured below), likely from frequent contact with those pages. The spotting diminishes greatly as you get into the heart of the book. Notably, the title given on the spine is “S. Fielding’s Socrates.” Xenophon, the primary author of the book, is nowhere to be found. Though this was probably done for a variety of reasons (e.g. brevity, ease of reference, cutting down on implied text), it suggests a level of independence on the part of the translator. It also renders the (purported) association between modern England and Hellenism even more explicit and direct. The impression is that Fielding is interfacing directly with Socrates — not merely by way of his lesser-known protege — and by extension, England with classical civilization.

Provenance of Production

Stop 1: Printer

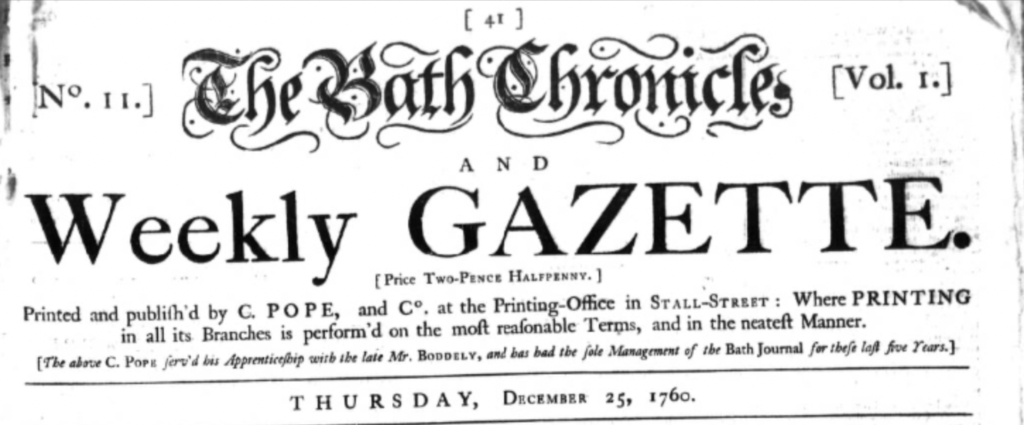

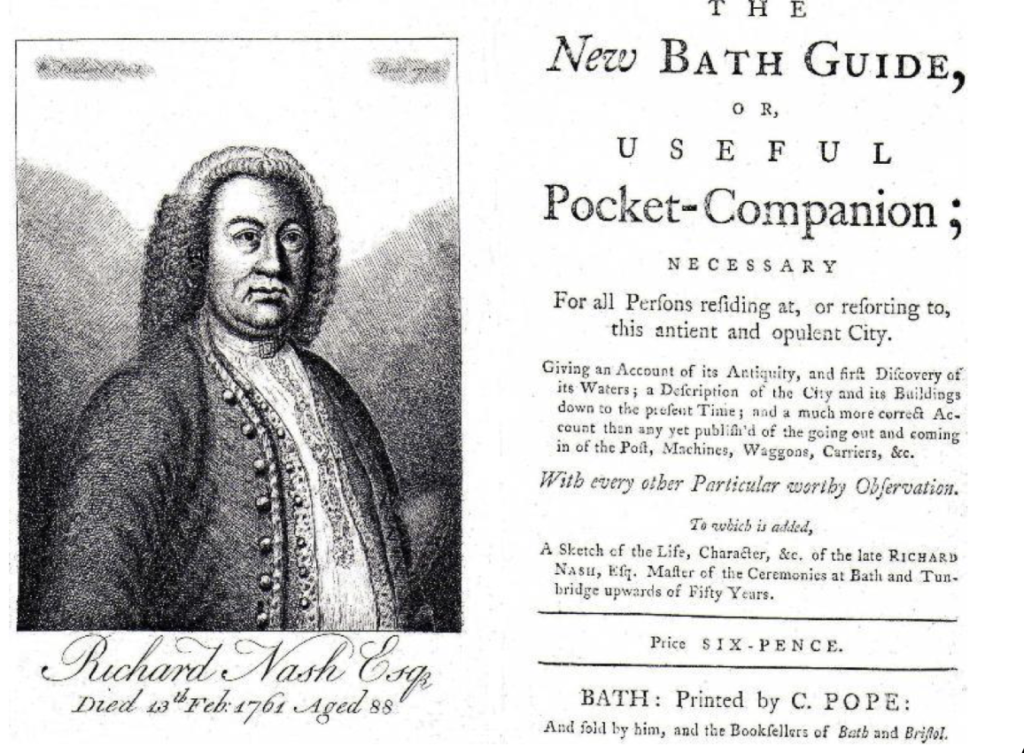

This edition was printed by a man named Cornelius Pope, in his print shop in Bath, England. Pope did his apprenticeship with Thomas Boddely, who was the proprietor of the newspaper the Bath Journal, and held a virtual monopoly on all kinds of printing in Bath, including “heraldry, shopkeeper’s bills, and other kinds of intaglio jobs”(4). Boddely died suddenly in 1754, leaving management of his shop to his right-hand man, John Keene. However, administration of the Bath Journal was assigned to a young Cornelius Pope (Ibid 25). Seeking more responsibility and freedom, Pope debuted his own print shop and rival publication in 1760, called the Bath Chronicle (Ibid 25). Somewhat confusingly for research purposes, there were two Bath Chronicle, both of which launched in 1760 and came out on Thursdays. The other Bath Chronicle was published by the erstwhile competitor, Stephen Martin, to Boddely/Keene’s grip on the Bath book trade; it was framed as a copycat move, to dupe readers (Ibid 25). However, Pope’s rendition of the Bath Chronicle ultimately dominated. Bath was known as a “spa town,” and its economy was premised heavily on travel. As such, the ability to print and sell Guidebooks at a regular rate was crucial. Pope recognized this and published The New Bath Guide in 1762, which included a frontispiece of a recently deceased Bath notable (pictured below), to legitimize his claim to the public and to “free” circulation of information (Ibid 26).

Sarah Fielding had moved to Bath in 1754, and was presumably aware of the politics and turnover in the Bath printing and publishing industry. She took a gamble by entrusting Pope with her translation of Xenophon’s Memoirs, since his shop had only been operative (independently) for a year. She expressed her confidence in Pope, calling him “an ingenious young Man lately set up that I believe will do very well” (Ibid 27). Bath historian Christopher Antsey attributes the delay in part to the unconventional mode of publication, which was contingent on (and indeed funded through) a list of subscribers — more on that to follow below (Ibid 27). Regardless, Pope’s bread and butter was newspapers and guidebooks, not books. Financial and political pressures (such as the 1757 Stamp Act and its limits on advertising) likely compelled him to print a book-length work (Ibid 21). He was never able to fully engage that market, though, and remained a newspaper and guidebook specialist.

*A Note on Binding*

This edition appears to be half-bound. The boards feel cheap and lack heft, although they are covered in decent leather. It seems that the popular 19th-century technique, “tree calf” binding, was on trial here (12). It seems botched, although this is entirely speculation. It falls victim to the classic industrial era bind: the sacrifice of structural integrity for cheap, swift production and ornate decoration. Although it was published in 1762 — before the height of the industrial age — these processes and pressures were clearly underway in England already. The first half of the book feels rather brittle when the pages are turned, and the latter half is so stiff almost to be unopenable (suggestive of gluing as opposed to sound needlework). It’s not clear whether this was bound in Pope’s shop or if it was outsourced to a binder. Based on the quality, assuming this is the original binding (and not a 19th-century “fixer-upper” mission), I’d say it was bound in-shop. Again, collapsing the different elements of the production process is a squarely 19th-century phenomenon, but Britain was quick to industrialize. It’s plausible that this book from 1762 presaged what was to come of the book trade in the following century.

Stop 2: Bookseller/Publisher

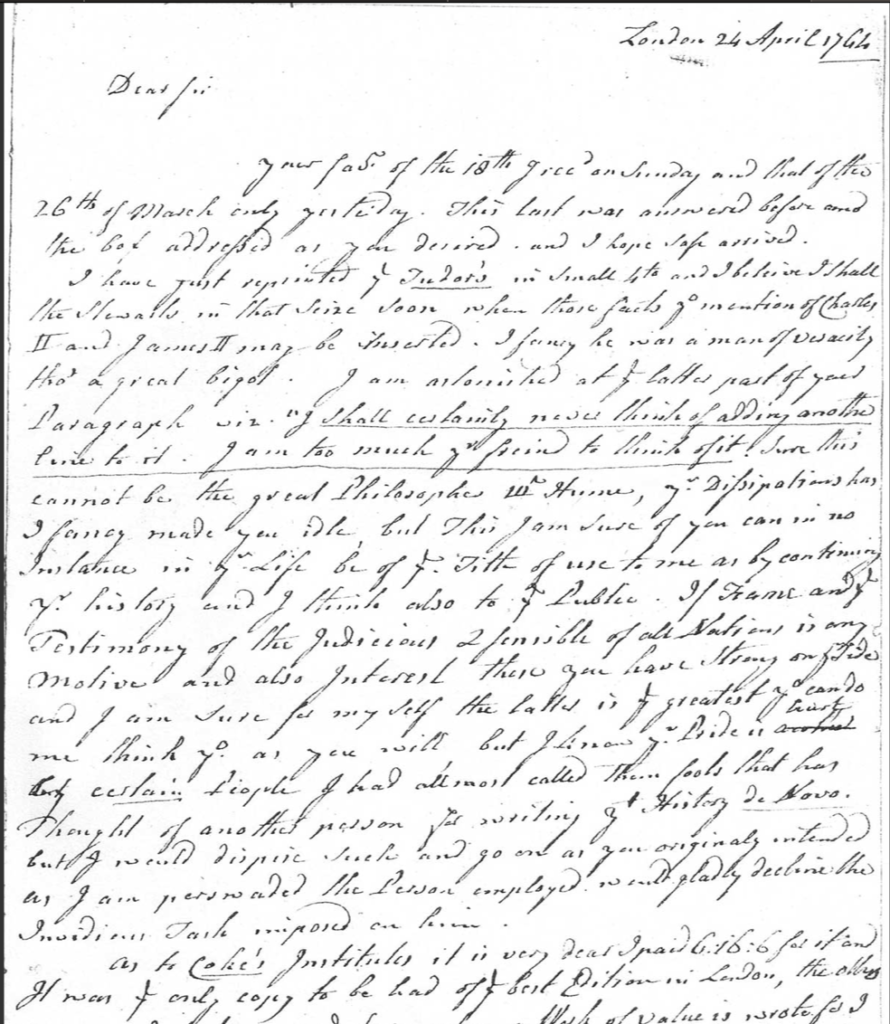

While printed by Cornelius Pope, the run was actually published and sold by Andrew Millar. Millar was prominent in the British book trade. He was not particularly well-read, but he was incredibly business-savvy and had correspondence with well-known authors and philosophers like Samuel Richardson and David Hume (letter from Millar to Hume pictured to the left) (13). One such connection was to Henry Fielding, a novelist and the brother of Sarah Fielding. Millar was first to publish some of Henry’s most lauded works, and this is presumably how he ended up selling Sarah’s translations of Xenophon (14). As a wealthy businessman, Millar also enjoyed traveling with his wife. They took long trips to Bath (Ibid). It’s here that he surely became aware of Cornelius Pope, perhaps by reading the Bath Chronicle.

*A Note on the Subscriber List*

The subscriber list is one of the stranger elements of the book. There are a total of 611 names. Most seem to come from the upper echelons of society. Many sound noble, and some have titles like “Reverend.” Subscriber lists were not common, even at the time of publication. A benefit of subscriber lists is that they act like insurance for a bookseller/publisher. The subscribers fund the book in part, which minimizes the risk for the publisher and printer (and they can know that they’ll at least break even on their own investment). Perhaps Millar insisted on this setup, since he was well-established in the publishing industry. Pope had just opened his print shop, and this was the first time Sarah was publishing under her own name. Regardless, the ordeal of getting enough people to “subscribe” likely slowed the pace of production.

The subscriber list is also strange because it seems to eliminate the need for a bookseller/publisher. Maybe there were more than 611 copies printed in the first run, and those additional ones were sold in Millar’s shop. Maybe I’m misapprehending the subscription list setup completely. Either way, the production of Memoirs was backed by Fielding herself, Pope, Millar, and the subscribers, whose support guaranteed that (at least) 611 copies would sell.

Provenance of Ownership

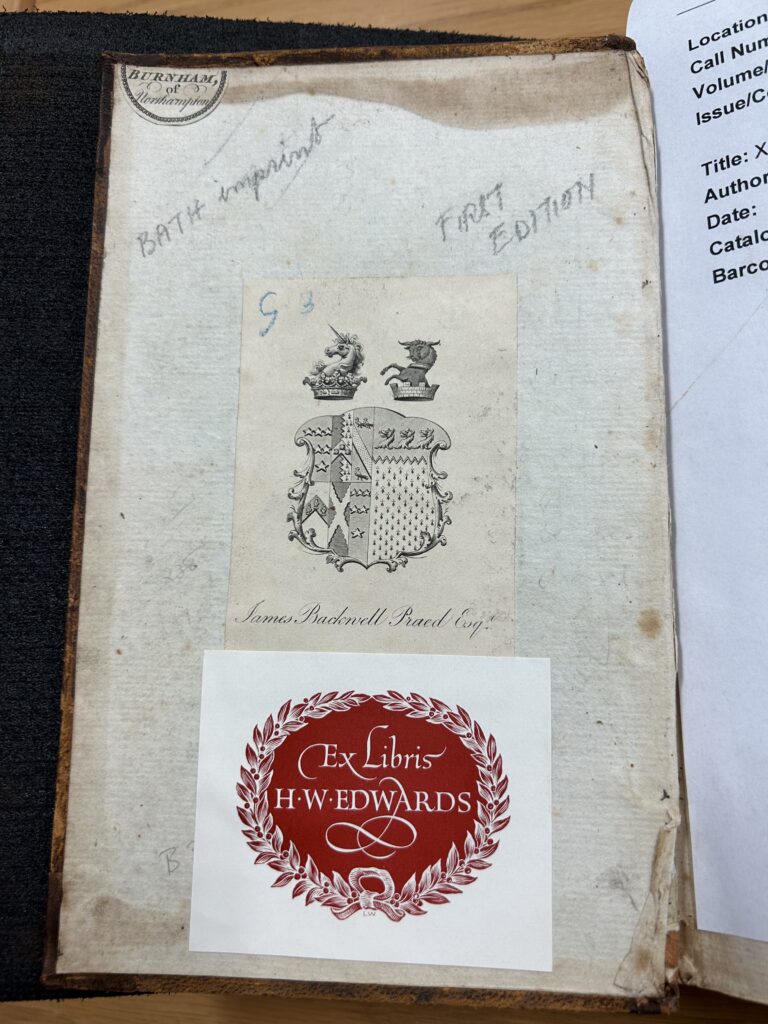

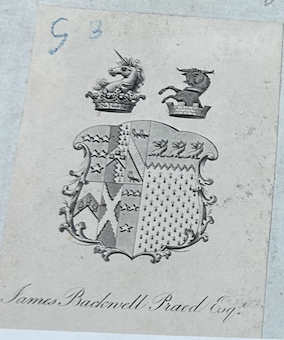

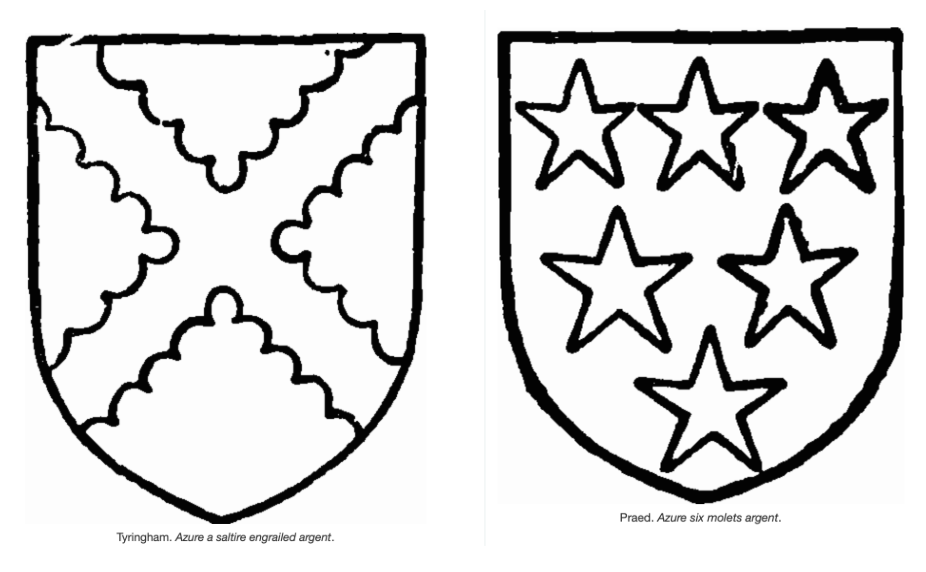

James Backwell Praed

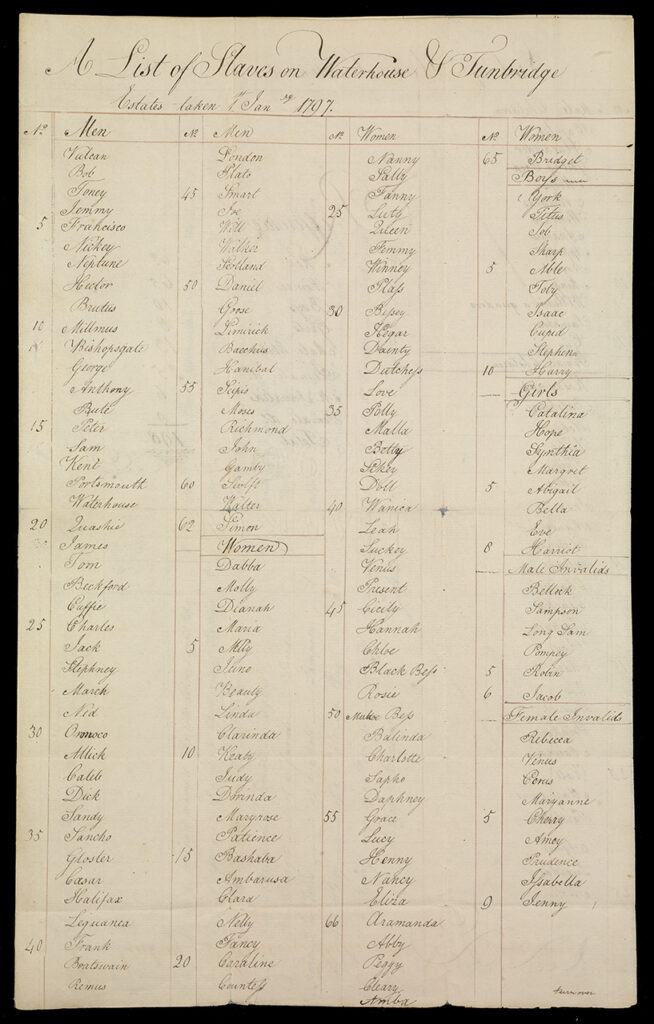

The first concrete mark of ownership is an armorial bookplate that reads “James Backwell Praed, Esq.” James (1779-1837) was the son of William Mackworth Praed and Elizabeth Praed (nee Tyringham). William Mackworth Praed was a member of the House of Commons and prominent banker (pictured left) (16). Elizabeth Tyringham was the daughter of Barnaby Backwell, who represented Tyringham of Buckinghamshire in Parliament (hence her last name) and who was also a banker (17). Elizabeth was descended from a line of nobles dating back to the 1000s. The family owned property known as the “Tyringham Manor,” which was passed down through the centuries. They also acquired two sugar and rum plantations in St. Andrew, Jamaica: the Tunbridge and Waterhouse Estates (18).

Barnaby Backwell (Elizabeth’s father, James’ grandfather) died young in 1754. Ownership of the plantations and Tyringham Manor passed to his last surviving brother, James Gibbon, who is described as an “absentee slave-owner” (Ibid). Gibbon passed away around 1791, and ownership of the estates then passed down to Elizabeth Tyringham, and therefore, William Mackworth Praed (20). William and Elizabeth swiftly began renovating the Tyringham Manor — a mansion on the historic land — which was described in 1782 as “neglected, but not wholly unfurnished” (21). They enlisted the help of respected architect Sir John Soane, and the house he built still stands today (and went on the market in 2013 for 18 million) (22). In part to finance this, the Praeds sold the two plantations in Jamaica around the turn of the century (23). A “plantation inventory” — a list of the names of those enslaved — is pictured to the left. It was drawn up in 1797, concurrent with the Praeds’ ownership of the plantation. This handwriting could belong to one of them.

James Backwell Praed likely lived in the mansion for a considerable period of time. Although he was a young adult when the renovation was finished, it was designed for extended family and a staff of servants. James was not as notable as his father or mother, but he followed in his father’s footsteps as a statesman, and became the Sheriff of Buckinghamshire in 1807 (24). He married Sophia Chaplin in 1823. In 1835, he was elected to the House of Commons, but his term was cut short in 1837 by his premature death (25). (His will is for sale online, but I feel sketchy about entering my debit card information there.) His wife and their 3 children survived him.

(Tyringham Hall today pictured to left).

The bookplate is in an elaborate armorial style. We can assume that James owned many books, as his bookplate is listed in WorthPoint, an online antiquarian marketplace (26). The seal is rich with symbolism. It most closely resembles the Chippendale Armorial style, which was popular in the mid-18th century (27). Both the Praed and Tyringham family coat of arms are present on the left half of the escutcheon. James’ son, William Backwell Praed, eventually changed the family surname to Tyringham by royal license. This perhaps reflects the higher prestige of the Tyringham name, and a desire to align himself with his paternal grandmother’s family. It could also be that William Backwell Praed/Tyringham wanted to distinguish himself from William Mackworth Praed, his grandfather.

Presumably, the original owner was one of those listed on the subscriber list. There are no instances of “Praed” or “Backwell” on the list, but a potential linkage to James Backwell Praed is in “Miss Susanna Mackworth.” She could be one of James’ paternal aunts or second cousins. James did have a cousin named Susan Mackworth Praed, who married around 1800 (28). Though that lines up with the fact that she was unmarried when the book was published (1762), it seems unlikely that this cousin is the Susanna Mackworth on the list, because that would be a very late marriage. What’s more plausible is that Susanna (and its derivative spellings) was a family name, like William, that was reused many times — making research frustrating. Another Susannah Mackworth (Stokes) was the cousin of James’ father William, but little is recorded about her, except that she lived from 1727-1794 (29). She would have certainly been married by 1762, and it would be strange for the subscriber listing to reflect her married surname (Mackworth) with an unmarried title (Miss). However, mistakes happen in print. She gave her name to her daughter, Susanna Mackworth Praed, but the latter was born in 1766, so it couldn’t be her (30). It’s also possible that the Susanna Mackworth on the list is related to James Backwell Praed in some way, since it was a family name, but has been otherwise lost to the annals of history. This is all speculation, anyway.

H.W. Edwards

The identity of H.W. Edwards remains a mystery in this book’s chain of ownership. The bookplate is ambiguous in several ways: Edwards is a common last name, especially in modern Britain and America, there is only a first and middle initial, and the bookplate itself looks both dated and recent. In my head, I imagined that H.W. Edwards would have intercepted the book before “Burnham of Northampton,” which was rather arbitrary but also based on the placement of the bookplates. As such, I neglected to look at the photos I took, and continued my research as if H.W. Edwards was the next owner. When I eventually had another look at the bookplate, I realized it’s a brilliant white — quite a jarring contrast to the yellowed parts of the book — and it looks like the work of a digital printer. For the purpose of showing my work, I’ll explain some of my (now) foiled theory.

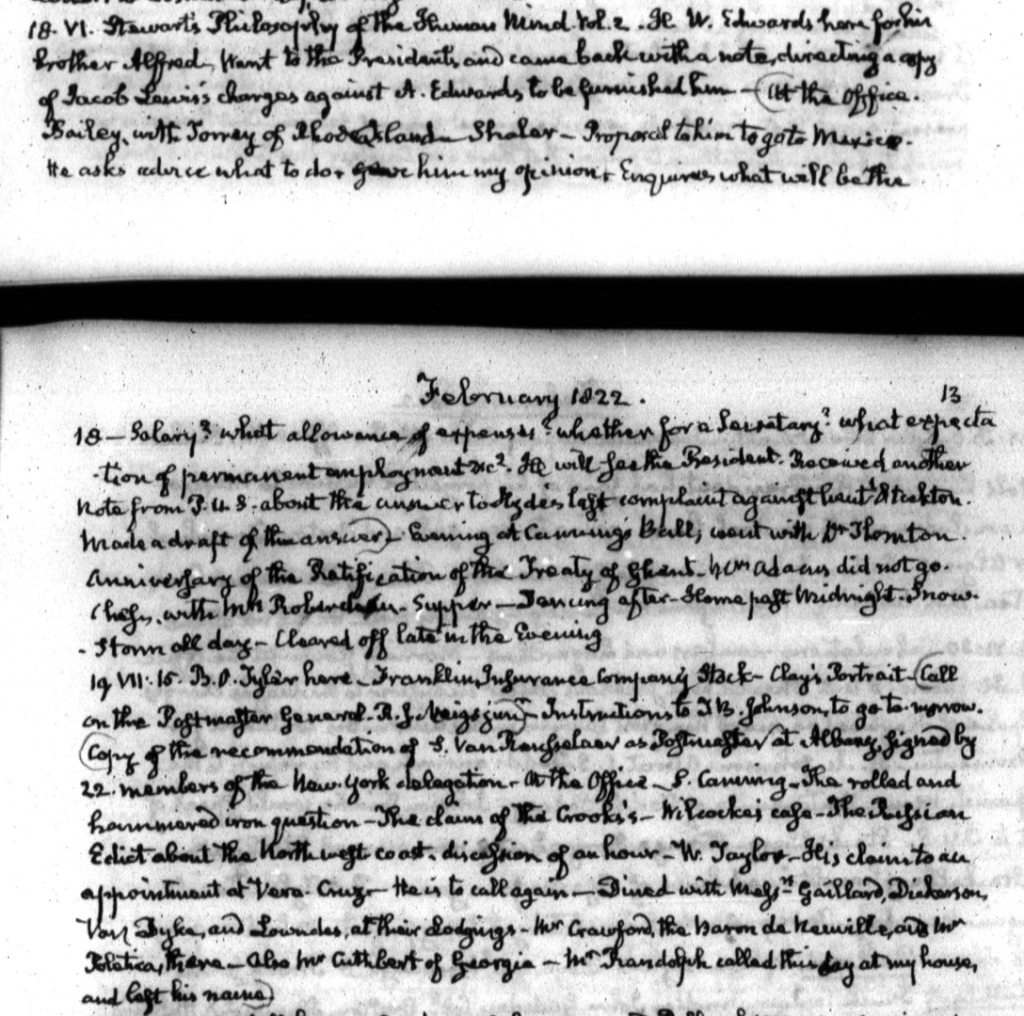

I was forced to make a lot of assumptions to have any chance of finding “H.W. Edwards.” I knew that the book eventually ended up in Northampton, Massachusetts (more on this owner to follow). I wagered that the book came across the Atlantic at some point, not long after James Backwell Praed’s death in 1837 — perhaps it was sold or gifted, as is sometimes done with the less important belongings of the deceased. I searched for something like “h.w. edwards 1800s new england,” and “h.w. edwards 1800s england.” I stumbled upon mention of an “H.W. Edwards” in John Quincy Adams’ personal journal entry from 1822. At this time, Adams was the Secretary of State for the Monroe Administration (31). I could verify who he was talking about because he mentions his brother “Alfred,” in connection to some recent legal accusations. I used this information to find the name, Henry Waggaman Edwards. In a later entry, Adams mentions “H.S.[sic?] Edwards,” as a “member of Congress from Connecticut,” again requesting papers regarding his brother Alfred (32). (The charges, whatever they were, were sufficiently “refuted” in the eyes of Monroe and Adams, and dropped).

Henry Waggaman Edwards was a member of the US House of Representatives in 1822, and then served in the US Senate before being elected Governor of Connecticut in 1833 (33). He was the grandson of Jonathan Edwards, the famous theologian. Although the Edwards family are most associated with Connecticut, Henry’s father, Judge Pierpont Edwards, was born and raised in Northampton (34). In my mind, this further solidified that Henry Waggaman Edwards owned the book, since it ended up in Northampton, and he had familial ties to the place. (Again, not realizing that Northampton was a pretty happening place in the 19th century) (35).

This all came to a roaring halt when I reviewed the images of the bookplate. Part of me still wants to believe that it belonged to Henry Waggaman Edwards, and that it was bleached or some other material trickery is at play. However, the gleam and HP-esque precision is undeniable. It would be cool if this book had belonged to Henry, as this would place it in a very interesting spot in American history, but it’s almost certainly not the case. I’ve tried to come up with other H.W. Edwards, but nothing has turned up. My inability to date the bookplate is a significant impediment.

Burnham of Northampton

The final mark of ownership is fairly cut-and-dried. It’s an institutional mark: the Mary A. Burnham School for Girls in Northampton, Massachusetts. In a sense, it’s still operational, though it was merged with four other prep schools in the area. Today, it’s known as the Stoneleigh-Burnham School (36).

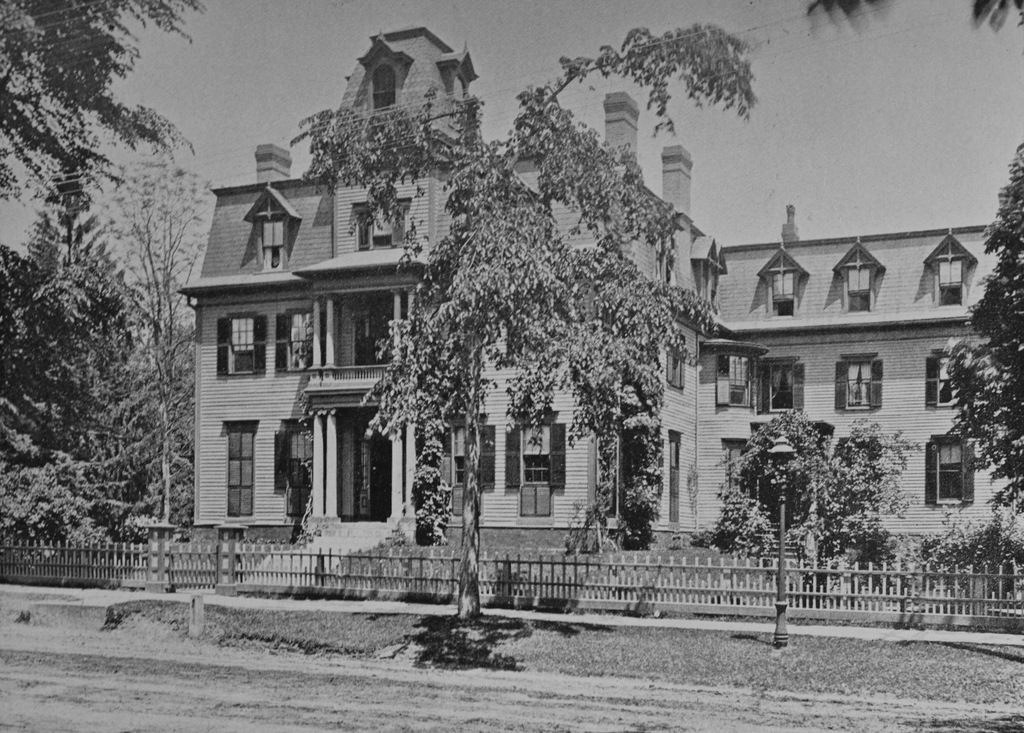

The school was founded in 1877 by Mary A. Burnham and Bessie Talbot Capen as the “Classical School for Girls.” It was intended to be a feeder school for the newly established Smith College (Ibid). After Mary Burnham’s passing in 1885, the school was renamed in honor of her. This remained its name until 1968 (Ibid).

The Mary A. Burnham School was originally located in a house — the former residence of Elijah Hunt Mills, Samuel L. Hinckley, and Jonathan and Julia Lyman. It was constructed in 1810 for Elijah Hunt Mills, who was a lawyer and politician. Mills served in the US House of Representatives from 1815-1819, and was appointed to fill a vacancy in the US Senate from 1823-1827, much like Henry Waggaman Edwards (their timelines and trajectories do overlap, to my chagrin). To add fuel to the fire, one of the next owners of the home — Jonathan Lyman, through his wife Julia — was a descendant of Timothy Dwight IV, one of Henry Waggaman Edward’s cousins. Julia Lyman’s other grandfather was Caleb Strong, who was a delegate for the US Constitutional Convention in 1787, where he would’ve encountered Pierpont Edwards (H.W.’s father). There are plenty of coincidences here, but they miraculously plot a logical roadmap for this book. I suppose circles were just that small in late 18th-century/early 19th-century New England.

Jonathan Lyman sold the house directly to Mary in 1887, and the school opened for enrollment that same year. By the looks of the stamp, the book was acquired by the Burnham School not long after — we know that it was after 1885, when the school changed its name. It was likely around the turn of the century, give or take a decade.

Michigan State University

This brings me to the final and extant owner of Fielding’s translation: the Special Collections at Michigan State University. It is unclear when and how this book made its way here, especially given the uncertainty around H.W. Edwards, and the possibility that he owned it sometime between the Burnham School and MSU. There could certainly be missing links on the chain of ownership, as well. MSU Special Collections was formally created in 1962, and it’s not unlikely that this book came to us after that date (thanks to the more organized/concerted effort to acquire and catalog old books). As aforementioned, the Mary A. Burnham School merged with the Stoneleigh-Prospect School in 1968. It’s possible that the merger necessitated a clearing-out of excess library inventory, and that the book was sold or given to a newly-established MSU Special Collections. It is also possible that H.W. Edwards — whoever he was — donated the book to MSU sometime in the 20th century, among many other theories. I almost wish that the information about where and when a book was purchased was recorded in the MSU catalog, or somewhere.

Other Marks of Provenance

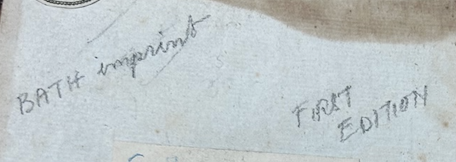

BATH imprint

This is on the front pastedown, next to the bookplates. It looks to be recent penmanship. I’m guessing that it was done by someone at MSU during the cataloguing process, to record that it was printed in Bath, England. Although it’s stated on the frontispiece, perhaps it was written to help more immediately identify that this is a Bath first edition (as there are multiple later editions in the library).

FIRST EDITION

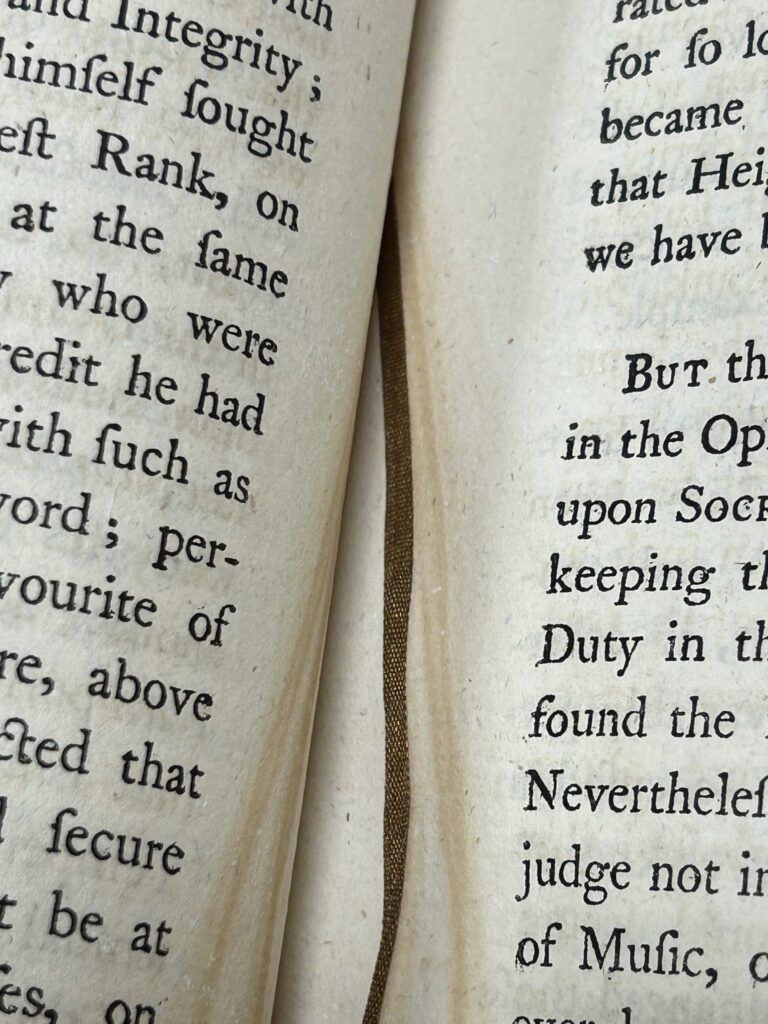

Bookmark Imprint

A particular mark of use in this copy is the bookmark pressed into the gutter between page 27 and 28. Since it’s hidden, it would be easy to not realize there’s a bookmark in this book at all. It has likely been wedged there for quite some time, judging from the discoloration marks around it.

Works Cited

Adams, John Quincy. “The John Quincy Adams Digital Diary.” Massachusetts Historical Society, March 26, 1822. https://www.masshist.org/publications/jqadiaries/index.php/document/jqadiaries-v33-1822-03-26-p026/dual.

Adams, John Quincy . “The John Quincy Adams Digital Diary.” Massachusetts Historical Society, February 18, 1822. https://www.masshist.org/publications/jqadiaries/index.php/document/jqadiaries-v33-1822-02-18-p018.

Antsy, Christopher. “Printing and Publishing at Bath, 1729-1815.” In The New Bath Guide, 119. Bath, UK: Ruton , 2008. https://historyofbath.org/images/documents/Georgian%20Imprints.pdf.

Ballotpedia. “Pierpont Edwards.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://ballotpedia.org/Pierpont_Edwards.

“Brief History of Northampton, Massachusetts – Historic Northampton Museum and Education Center.” Accessed October 31, 2023. http://www.historic-northampton.org/highlights/brief.html#:~:text=19th%20century%20Northampton%20drew%20visitors,%22picturesque%22%20%2D%20the%20ideal%20middle.

“Details of Estate | Legacies of British Slavery.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/estate/view/14535.

“Details of Relationship | Legacies of British Slavery.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/relationship/view/2058778835/2146638317.

“Early 19th Century:The Era of Industrialization | History of Binding | Exhibits | MSU Libraries.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://lib.msu.edu/exhibits/historyofbinding/early19thcentury.

“FamilySearch.Org.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/K8WX-89S/susanna-mackworth-praed-1766-1856.

Garwood, Rebecca. “Sarah Fielding (1710-1768) .” Chawton House Library, n.d. https://chawtonhouse.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Sarah-Fielding.pdf.

geni_family_tree. “Susannah Stokes,” 1727. https://www.geni.com/people/Susannah-Stokes/6000000100940879839.

“John Quincy Adams – People – Department History – Office of the Historian.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/people/adams-john-quincy.

Michael R. Thompson Rare Books. “Xenophon’s Memoirs of Socrates. With the Defence of Socrates, before His Judges. Translated from the Original Greek… by Sarah Fielding, Xenophon on Michael R. Thompson Rare Books.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.mrtbooksla.com/pages/books/7692/sarah-fielding-xenophon/xenophon-s-memoirs-of-socrates-with-the-defence-of-socrates-before-his-judges-translated-from-the.

National Governors Association. “Henry Waggaman Edwards,” January 7, 2015. https://www.nga.org/governor/henry-waggaman-edwards/.

“Parishes : Tyringham with Filgrave | British History Online.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/bucks/vol4/pp482-485#h3-0002.

“Parishes : Tyringham with Filgrave | British History Online.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/bucks/vol4/pp482-485#h3-0002.

“Parishes : Tyringham with Filgrave | British History Online.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/bucks/vol4/pp482-485#h3-0002.

“School Legacy.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://sbschool.org/welcome/school-legacy.

“Scottish Publishers and English Literature: Andrew Millar (London) 1728.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://victorianweb.org/history/scotland/3.html.

Strahan, Derek. “Burnham School, Northampton, Mass.” Lost New England (blog), July 18, 2018. https://lostnewengland.com/2018/07/burnham-school-northampton-mass/.

“Styles.” Accessed October 31, 2023. http://www.bookplatesociety.org/styles.html.

“Summary of Individual | Legacies of British Slavery.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146650925.

“The Manuscripts.” Accessed October 31, 2023. http://www.millar-project.ed.ac.uk/manuscripts/html_output/.

“Tyringham Hall – HouseHistree.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://househistree.com/houses/tyringham-hall.

“Will of James Backwell Praed of Tyringham , Buckinghamshire,” February 8, 1837. PROB 11/1873/135. The National Archives, Kew.

Worthpoint. “Ex-Libris Bookplate. James Backwell Praed Esq. Please See Large Pics. | #454399172.” Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/ex-libris-bookplate-james-backwell-454399172.

By Anna LePage for HST 475. Fall Semester 2023