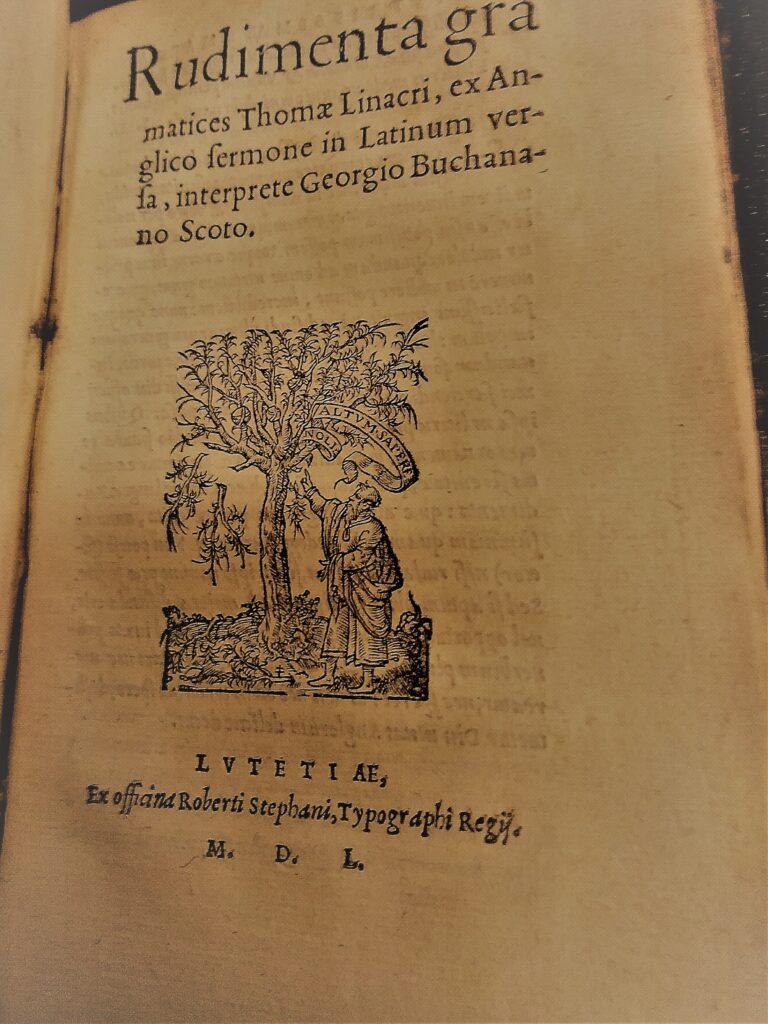

Thomae Linacri, ex Anglico fermone in Latinum versa, interprete Georgio Buchanano Scoto / (The Rudiments of Grammar to Thomas, Linacri, turned into Latin from the English, as expounded by George Buchanan) / Thomae Linacri Britanni de emendata structura Latini sermonis libri sex : emendatiores : index copiosissimus in eosdem (Thomas Linacre’s structure of the Latin language, six, corrected index abundant in the same)

Linacre, Thomas (1460-1524) Rudimenta gramatices Thomae Linacri, ex Anglico fermone in Latinum versa, interprete Georgio Buchanano Scoto / (The Rudiments of Grammar to Thomas, Linacri, turned into Latin from the English, as expounded by George Buchanan) / Thomae Linacri Britanni de emendata structura Latini sermonis libri sex : emendatiores : index copiosissimus in eosdem (Thomas Linacre’s structure of the Latin language, six, corrected index abundant in the same) Lutetiae [Paris]: Roberti Stephani, 1550. Call No. : XX PA2311.L56 1550

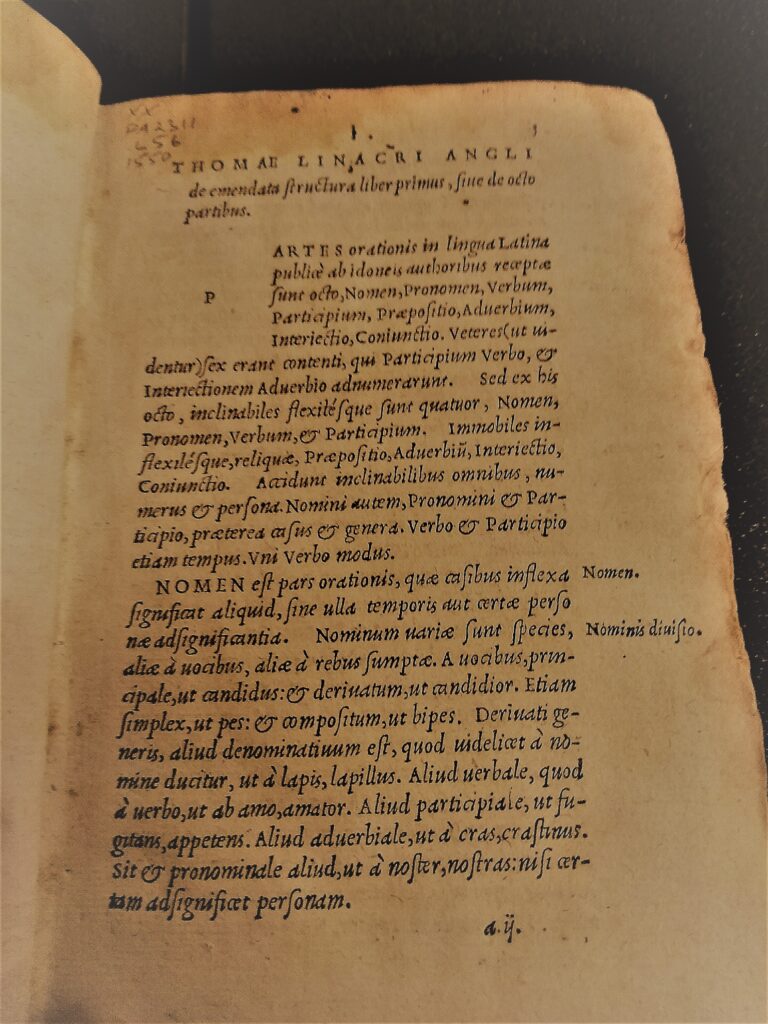

The book is 17 cm, octavo, which was a common size for publications between the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The text is an unmediated volume containing two separate texts. The first portion is George Buchanan’s translation and interpretation of the primary text and includes Spanish humanist, Juan Luis Vive’s ‘De ratione studii puerilis‘ with the English translation roughly meaning ‘On the Right Method of INstruction for Children’ (p. 100 – 116). This first secton contains 116 numbered pages with unpaginated. The second portion of this publication is the actual Latin textbook written by Linacre. It contains 404 pages and 44 unpaginated.

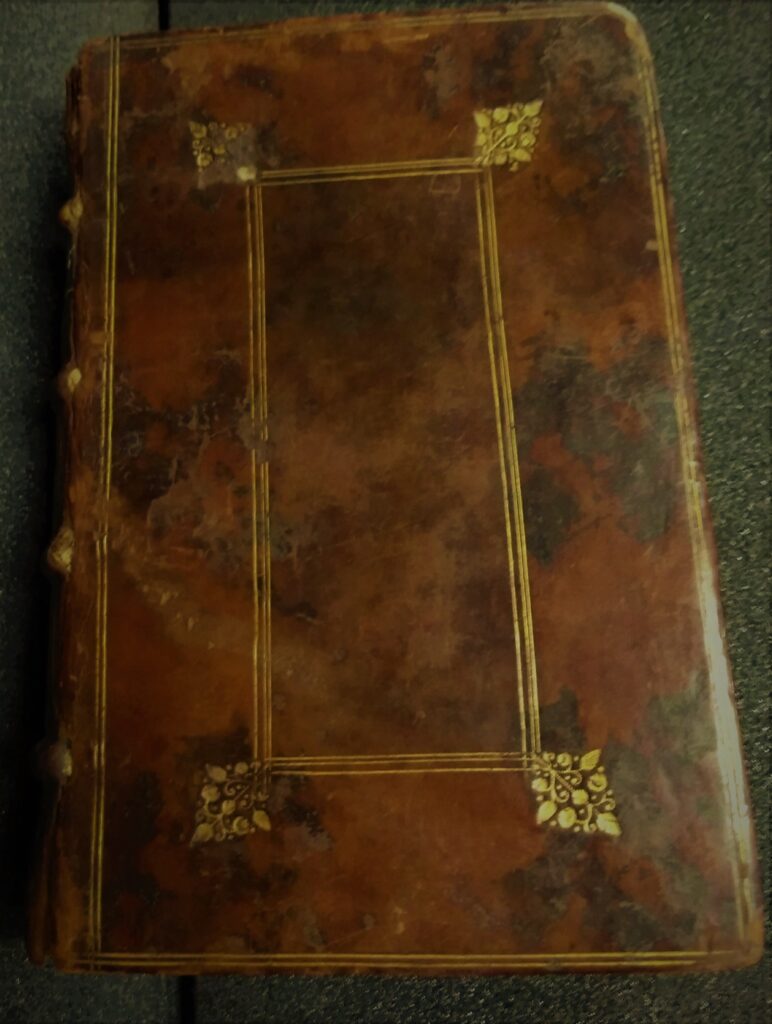

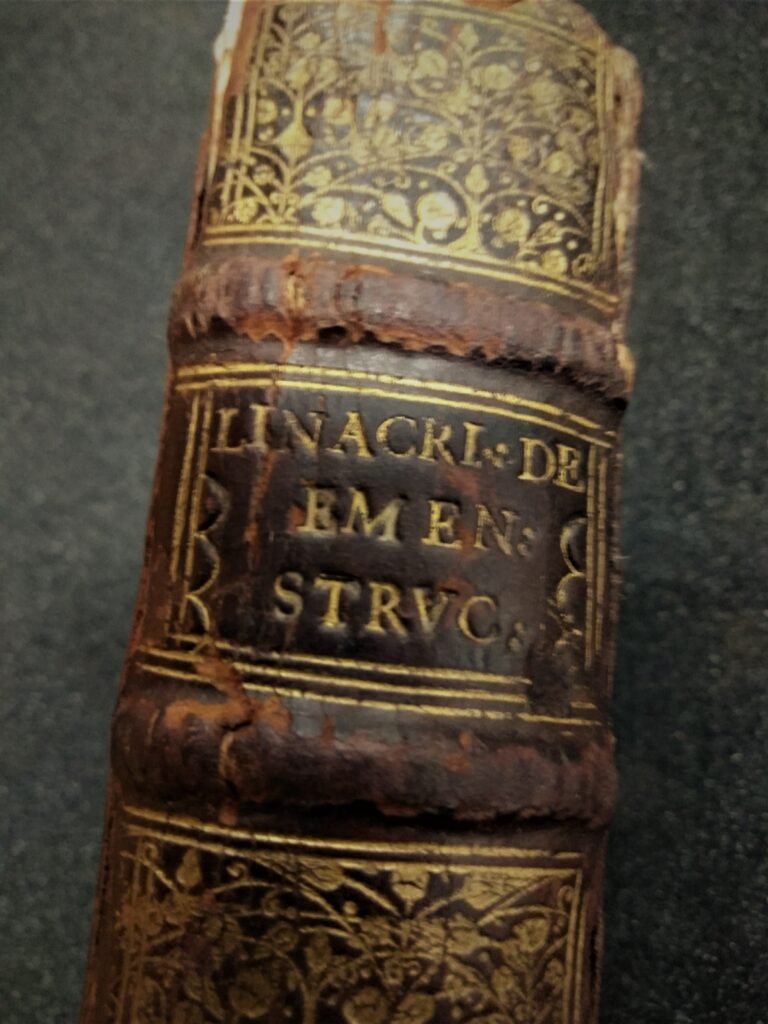

The textbook is marbled and the cover is mottled calf, possibly dyed. The spine has 4 raised bands which are situated between intricate spine-tooled designs composed of gold. The Latin translation of Linacre’s last name (Linacri) followed by the shortened version of the title: ‘De Enem Struc’ Is centered between the first and second top bands of the spine. The front and back boards are panelled in gold at their center.

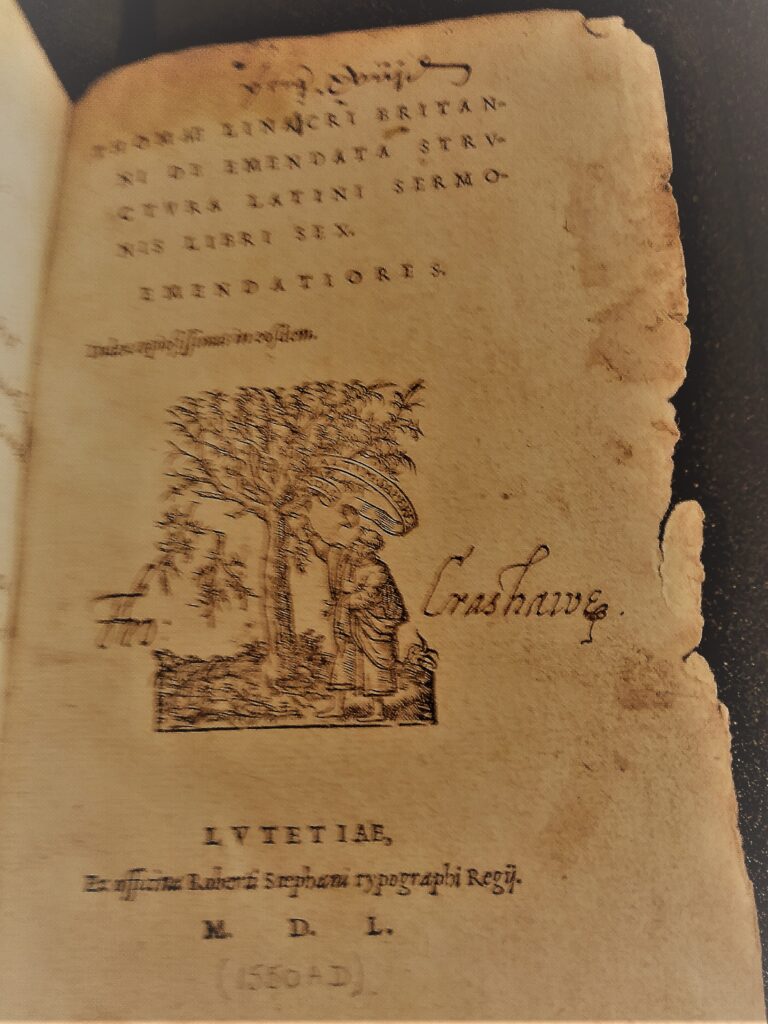

The book includes a colophon on the final leaf recto and the final leaf verso: Excudeba Rob. Stephanus, Tupographus Regius, Parisiis, ann. MDL III Cal. Decem. and Excudebat Robertus Stephanus typographus regius, Lutetiae, VI, id. Mar. an. MDL. both title pages include a woodcut print

The George Buchanan translations and interpretation of the eight volumes first appeared in 1533 and an interpretation is what is contained in the first section of this publication of this final Estienne edition of the book, which appeared in 1550.

This 1550 edition wears evidence of its age but it is in good condition. The book has undergone obvious use by its owners. The mottled calf boards and all edges are bumped and rubbed, however, the gold- tooling on the boards and spine do not present significant damage. The head band and tail are cracked, fraying, and their binding to the text and the hinges are sprung.

The interior of the front board has a pastedown with foxing and is partially torn and peeling away from the margins. The fly-leaf and preliminary pages have chipping and foxing. The textblock as a whole foxed, cockled crimped, and the page edges and ends are yellowed and scuffed.

The author, Thomas Linacre (1460-1524) is identified by contemporaries as a humanist scholar. He was exceptionally brilliant and was quite motivated and molded by the Renaissance. He studied at Padua where he attained a degree of doctor of medicine with distinction. Numerous institutions are named after him including Linacre College and The King’s School, Canterbury.

Despite his education in medicine, his only medical publications were translations. He translated Greek, English, and Latin and published numerous works.

Linacre’s ‘Rudimenta gramatices’ was originally published in Latin in 1524 in London and a total of eight Estienne volumes were published between 1527 and 1550 with this publication being the final volume. These were so named after Robert Estienne (printer). George Buchanan was responsible for the first English translation of Linacre’s work throughout the 16th century. At least 25 editions of these texts were published between 1512-1600.

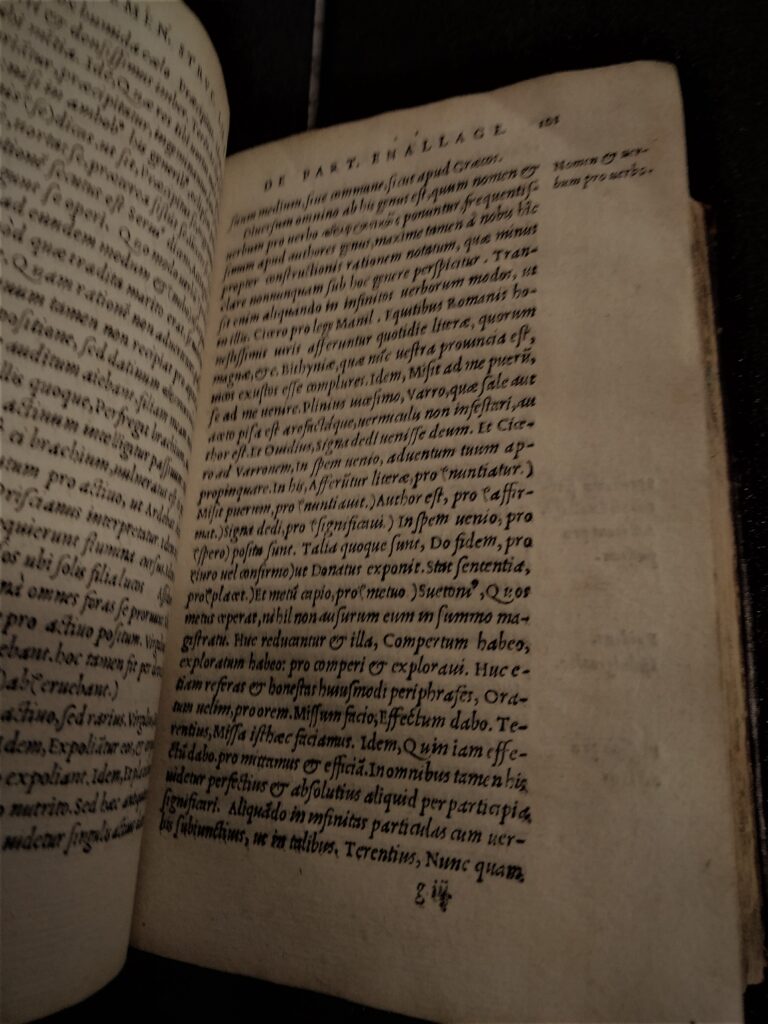

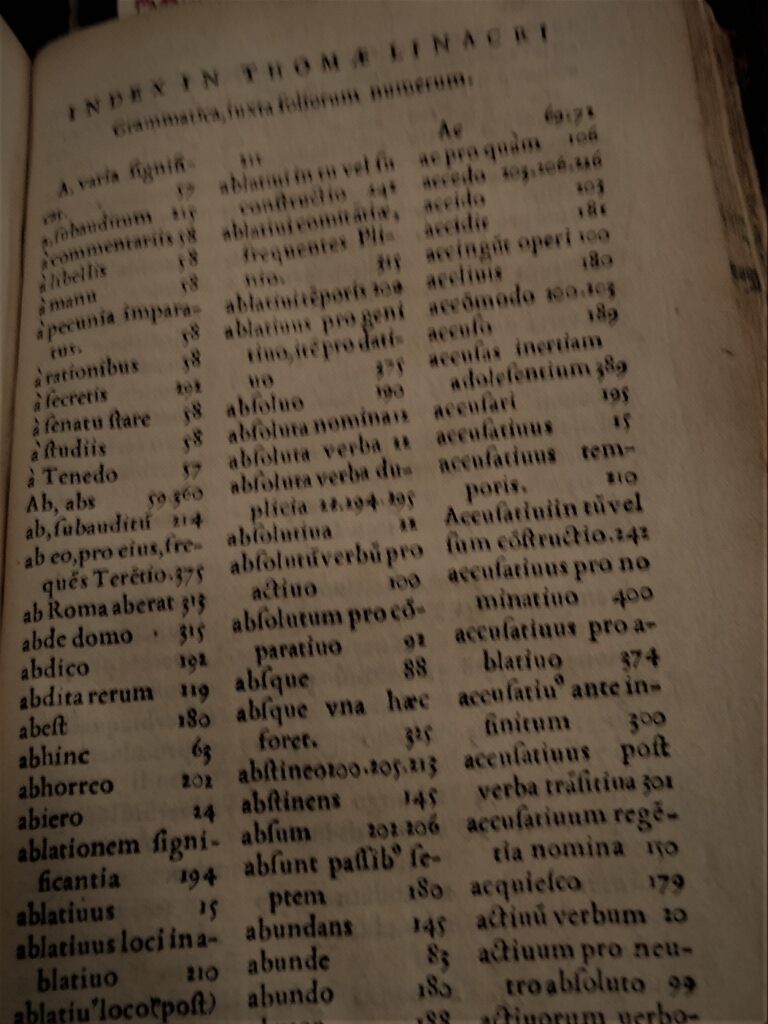

This book was utilized as a textbook and study guide by both students and educators. It is primarily organized in paragraph form with some pages of columnized text. There are running heads indicating the topic covered on the top margin of each page. It includes an index on the back, division of each topic covered with chapters, and is written exclusively in Latin. The fonts vary depending on if the words are indicating a heading or the topic’s content. The font is smaller and more decorative whereas the titles, heading, and other identifying words are in a Roman-style font with every letter capitalized. Roman Numerals are used whenever a number is indicated in the text with the exception of the page numbers.

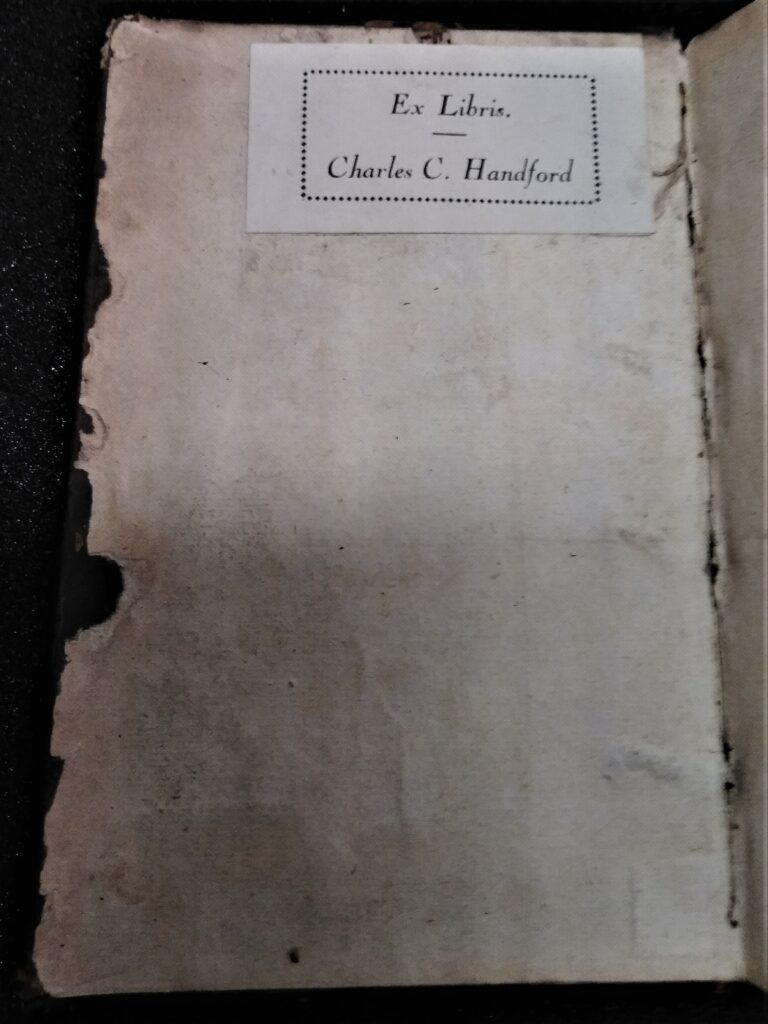

Indications of provenance in this book include a bookplate on the front board pastedown belonging to Charles C. Handford with the words ‘Ex Libris‘ printed above his name. The Latin term ‘Ex Libris’ can be translated as ‘From the books of‘, which was a common phrase printed on bookplates.

Although it is simple with a basic border, it is significant because it identifies one of the book’s former owner. Unfortunately, there is no date on or around the bookplate so it would be difficult to determine if this gentleman was an original owner. It should be noted that the book was printed without a binding, which was often personalized by the owner. Because of the book’s age, it may be difficult to determine if the binding this book possesses is original or not.

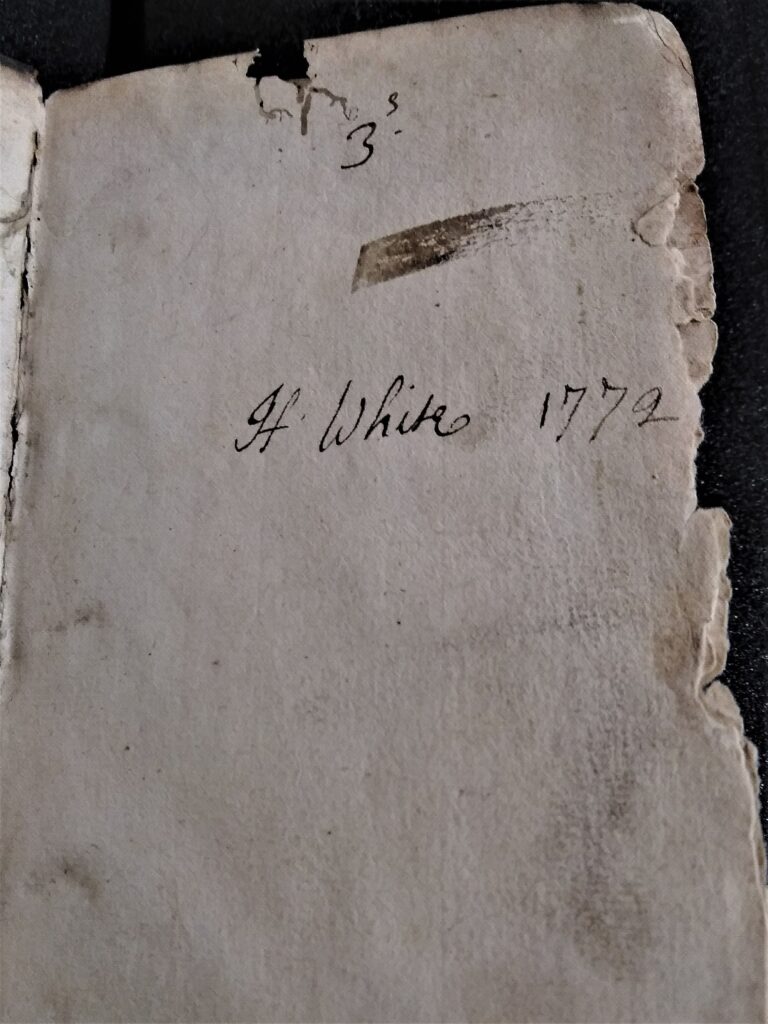

Additional evidence of ownership is indicated with a hand-written inscription in ink by H. White which includes the date 1772. Due to the fact that the date indicated by White is over 200 years later than when this book was published, he is an unqualified candidate for ‘original owner’.

The second half of the publication has a title page as well with Thomas Crashawe’s signature at it’s center. Due to the fact that this signature evidently belonged to a schoolmaster and the signature’s at the front of the text did not, it seems reasonable to suggest that the indications of provenance were added later or at the very least by owner’s of the book who was not necessarily a formal student using the text for study or a schoolmaster, which Thomas Crasawe was, using the text to teach. It is possible that they were more interested in the Buchanan interpretation at the front and were using it to self-study Latin. Since the current binding of this book was added later, it is possible that these two texts were completely separate, rather than published together. They may not have been published with an intent to bind them simultaneously, rather, the introduction was a separate ‘reference guide’ for this book and the owner who bound it wanted the texts compiled.

Thomas Crashawe was a 16th-17th century schoolmaster and thus could have been the owner of the actual textbook (perhaps with a different binding that did not include Buchanan’s work) and that is why his signature is on this title page rather than the one that precedes Buchanan’s work. Another possibility is that Crashawe felt it more appropriate to have his signature indicated on the title page of Linacre’s text specifically.

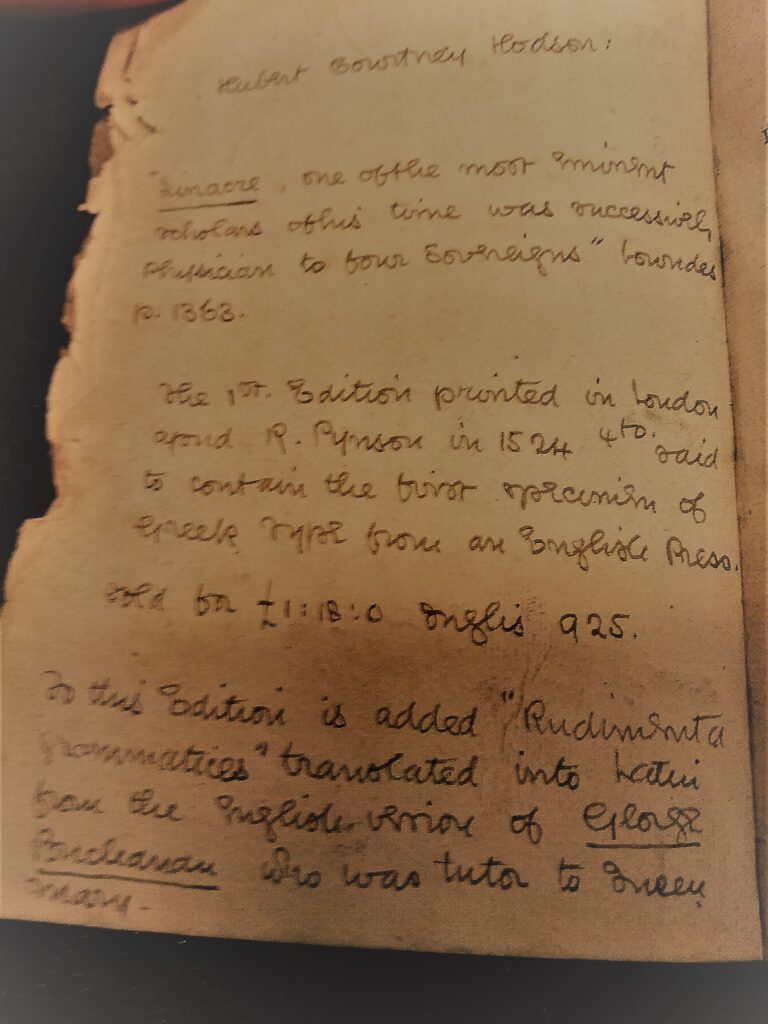

Further provenance evidence is this hand-written biographical note by Hubert Courtney Hodson (1847-1924). It is written on the second fly-leaf and includes his autograph. It is a short summary of Linacre as a scholar and some information about the book.

Jess Tourtillott

Undergraduate Michigan State University

‘History of the Book’ – Professor L. Brockey – HST 475

SOURCES

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Thomas Linacre.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, INC., 12 Aug. 2010, www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-Linacre

MSU Library Catalog – RBSC